Before this season, Nick Madrigal had spent just one inning at third base. It was in a showcase game; he was a high schooler. Madrigal played a fair bit of shortstop at Oregon State, but he has always primarily been a second baseman. Then in December, the Cubs signed Dansby Swanson, bumping Nico Hoerner over to second and Madrigal into a utility role.

Madrigal took the change in stride. He started a long toss regimen to improve his arm strength, and said all the right things to the press:

Bench coach Andy Green even flew out to Arizona to spend a week helping him get up to speed at the hot corner. All of that work seems to have paid off. So far this season, Madrigal has spent 53 innings at second and 303.2 at third. As a third baseman, DRS and OAA both have him at +4, DRP has him at +1.1, and UZR has him at -0.1. Again, that’s after exactly playing exactly one inning at the position when he was a teenager.

It looks like Madrigal’s regular playing time at third is coming to an end, though. Patrick Wisdom is returning from the IL, and Madrigal just started his own IL stint due to a right hamstring strain. It’s a disheartening development for many reasons: Because he needed season-ending surgery on that same hamstring in 2021; because it makes his spot on the Cubs’ roster even more precarious; because he was on pace to have the most productive season of his young career; and because he does something really fun when he plays third base. I’ve been struggling with how to put it into words, so before I make my attempt, let’s see if you can spot it for yourself.

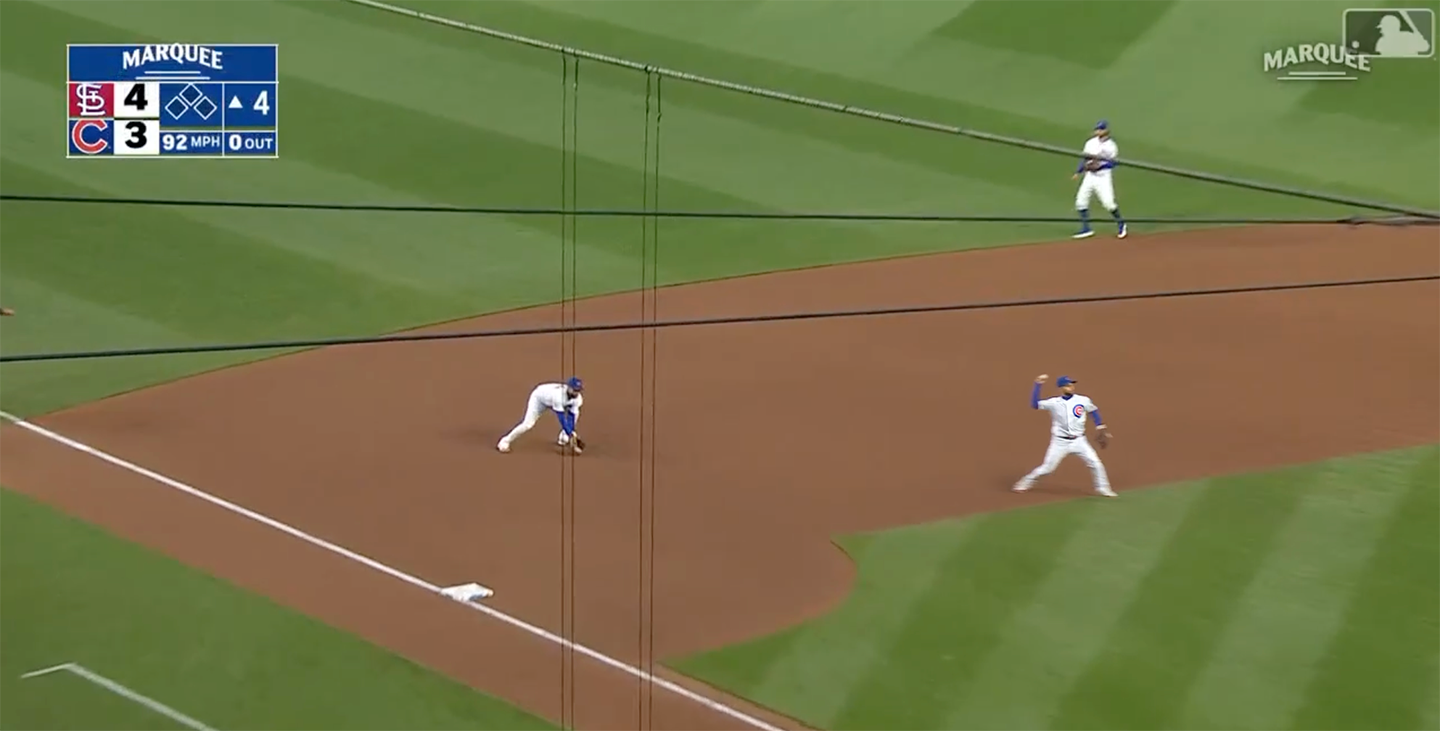

I don’t have a good sense of whether or not you’ll notice what I want you to notice. Maybe you saw it right away. Maybe you’re a Cubs fan and you already noticed it earlier this year. Or maybe it’s the kind of thing that you don’t notice until someone points it out, and then you can never not notice it. To make it a little easier, I combined two frames from that clip: I took the moment when Madrigal fielded the ball, then I added the moment when he threw it over to first.

Those two Nick Madrigals are in very, very different places. The first one is fielding the ball in a normal position roughly 15 feet behind the bag. Somehow the second one is way over on the right, about to make his throw with a foot on the infield grass. That’s a whole lot of infield to traverse right in the middle of a routine groundout.

This article is about how Madrigal got all the way from all the way from point A to point B. And the answer is that, well, he sort of… scampered.

Madrigal fielded the ball and essentially just started running over to first base before he actually threw the ball. This was not an isolated incident. It turns out that when he fields a groundball at third base, Madrigal doesn’t just set his feet and fire to first; he likes to get a running start.

I noticed tendency this a few weeks ago, and since then I’ve gone back and watched every groundball Madrigal has ever fielded at third base (a research technique known as “The Full Epstein“). In the vast majority of those attempts, he significantly cut down the distance to first before getting rid of the ball. Over the last couple days, I have watched a lot of third basemen field a lot of groundballs. Nobody else does it the way he does it.

The clip above consists of seven different third basemen, including Madrigal’s teammate Wisdom, making plays on nearly identical groundballs. All of them were hit between 89–91 mph and at a launch angle between -4 and -2 degrees. All were hit right at the third baseman for routine force outs with the bases empty. Madrigal is first, and he gets his classic running start, taking eight steps before he throws. Every one of the next six players fields the ball, shuffles twice, and lets it go.

Madrigal is playing the position differently than every other third baseman. I picked that play in particular because it was a box standard groundball, but I could’ve chosen plenty of others. Here’s a series of 10 different plays where he gets a running start, shortening the distance before he throws:

I don’t know why, but I find Madrigal’s tiny sprint toward first base incredibly endearing. The way he churns his feet the moment the ball hits his glove, the way he shuffles, sometimes even hopping twice in a row on his right foot before he goes into a double crow hop, the way he clicks his heels like Dick Van Dyke — I can’t stop watching it. I’m not even sure whether Madrigal is aware that he’s doing this. He’s kind of like a quarterback climbing the pocket before he fires downfield.

Madrigal is traveling a significant distance, too. Let’s go back to the first clip I showed you. If you’re anything like me, you’re curious about exactly how far he traveled between catch and release. Luckily, the 6-foot-1 Swanson is hanging out in the background. We can use him as a handy, handsome measuring stick.

We’re looking at roughly 4.5 Dansby Swansons, so something along the lines of 27.5 feet. Madrigal fielded the ball, nearly ran for a first down, then threw Andrew Knizner out at first base.

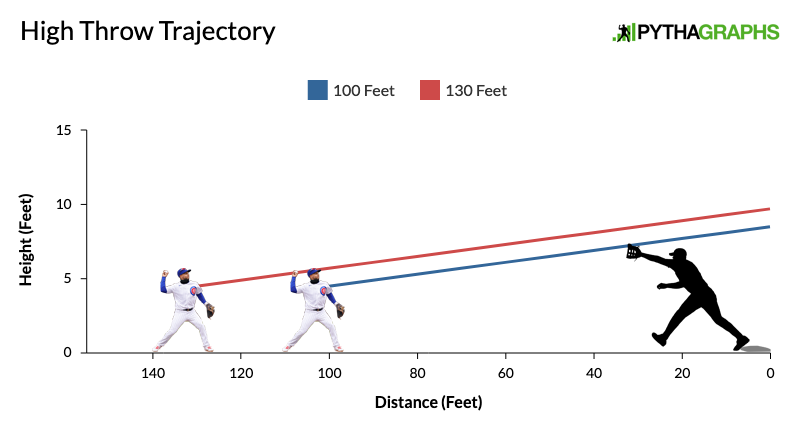

Generally speaking, cutting down the length of your throw isn’t a bad idea. If you’re off target, the farther away you are from first base, the bigger your miss will be. To demonstrate, I constructed a crude thought experiment with the help of my friend Pythagoras. In our experiment, the third baseman unleashes a high throw. He releases the ball at a height of 4.5 feet, and it travels a trajectory of 7.7 degrees.

When the third baseman is throwing from 100 feet away, the high throw is no problem. But push him back 30 feet, and the throw has time to rise another 1.2 feet. Even our gargantuan first baseman can’t snag it at that height.

That’s generally speaking. Now let’s talk specifically about Madrigal. When I watched all of his throws to first, I classified nine of them as at least somewhat off target. When taken together, they paint a very clear picture. I couldn’t fit them all in the supercut below, but would you care to guess what all nine have in common?

Every single bad throw Madrigal has made from third to first has been on a play where he didn’t get his normal seven-step running start. He still managed two crow hops on a lot of them, but it wasn’t the full routine that he prefers. I do not think that this is a coincidence. Running the ball over to first is working, and I don’t think he should stop doing it. Much like the Sundance Kid, Madrigal is better when he moves.

To be clear, I am not saying that Madrigal has a weak arm — just that he’s more likely to make a mistake when he’s forced to plant and make a long throw. Per Statcast’s throwing metrics, his 84.5 mph average and 86.4 mph max put him right around the middle of all qualified third basemen (though he might be juicing that number a bit by making so many throws with the benefit of a running start). It’s possible that he plays so shallow to compensate for his arm; at 115 feet, only Ke’Bryan Hayes, Hanser Alberto, and Yoán Moncada play shallower. But his range is still grading out fine, and he’s yet to yield an infield single on a bang-bang play. It’s not really holding him back.

He’s got enough arm to set his feet make the long throw when he needs to. All the same, I do think that he might be a little bit daunted when he looks up and sees how far he is from first base. Maybe that’s just what comes from spending your whole life on the other side of the diamond.

If you only look at the plays where he’s making a short throw, Madrigal is a completely different player. Watch what he does when the play is at second base or home plate:

This Madrigal is quick and decisive. He’s catching, planting his feet, and firing strikes. He’s getting rid of the ball in a hurry.

I think there are a bunch of things going on. Madrigal isn’t completely comfortable making the long throw, and whether it’s a conscious decision or he’s just doing what feels right in the moment, he’s found a way to avoid it most of the time. In order to make that work, he’s got to trust the clock in his head. He always knows how much time he has to get the baserunner, and he’s very comfortable using every last bit of it. So far it’s worked out well for him. The ancillary benefit for the rest of us is that it’s really fun to watch.